What does “organic” mean?

Organic refers to how farmers grow and process food. Organic farming methods differ from conventional farming in several ways:

- Conventional farming uses chemical fertilizers to promote plant growth, while organic farming employs manure and compost to fertilize the soil.

- Conventional farming sprays pesticides to get rid of pests, while organic farmers turn to insects and birds, mating disruption, or traps.

- Conventional farming uses chemical herbicides to manage weeds, while organic farming rotates crops, hand weeds, or mulches.

- When raising animals, conventional farmers give animals antibiotics, growth hormones, and medications to spur growth and prevent disease. Organic farmers feed their animals organic feed and allow them to roam. They also will make sure the animals have a balanced diet and clean housing.

The

U.S. Department of Agriculture certifies organic products according to strict guidelines. Organic farmers must apply for certification, pass a test, and pay a fee. It’s important to note that this means not all organic foods become certified, even though all certified food is organic.

If you pick an item off the shelf and see the “USDA Organic” label, it means that at least 95 percent of the food’s ingredients were organically produced. The seal is voluntary, but many organic producers use it. Products that are 100 percent organic are labeled as such and given a small USDA seal. Some product labels may also state that the product was “made with organic ingredients,” which means the product contains at least 70 percent organic ingredients.

Is organic better?

Shoppers may choose organic foods for a variety of reasons. There are certainly environmental reasons to go organic. According to USDA guidelines, organic farming practices are designed to reduce pollution and conserve water and soil. They do not release synthetic pesticides, which can harm wildlife, and they also seek to preserve biodiversity and local ecosystems.

Many people choose organic foods to avoid any risks associated with the pesticides, herbicides, and other chemicals used in conventional farming. Parents may be concerned that exposure to these chemicals might harm the development of their children, and therefore they

choose organic. Studies appear to

support the fact that organic diets lower children’s exposure to pesticides.

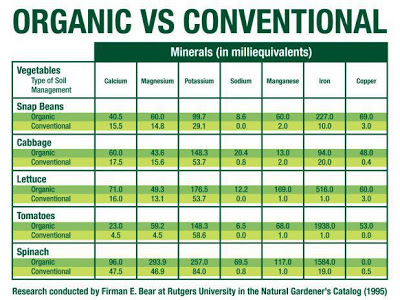

As for organic food being healthy, some studies, including one at

UC Davis, have demonstrated higher amounts of nutrients in some varieties of organic foods. Another

study from Newcastle University in England showed organic milk contained 67 percent more vitamins and antioxidants, as well as more Omega-3s and Omega-6s (“healthy” fat) than conventional milk. Organic foods do not contain any additives or preservatives, and are not genetically modified. And when you buy organic, you’re also bypassing antibiotics and hormones given to animals in conventional methods, added to the fact that these animals are also treated in a more respectful and humane way under organic standards.

Controversy exists over whether

all organic foods carry substantial benefits over their counterparts—organic onions, for example, might not be much different from their conventional cousins when it comes to health benefits—but in all cases, organic means the foods were grown on farms with USDA guidelines.

Why it costs more

The biggest criticism of organic food is its cost. There are several reasons it’s more expensive. Organic farmers pay more for organic animal feed, and the farming is more labor intensive, since farmers avoid chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Because farmers don’t use herbicides, for instance, they rely more on hand weeding. And since they avoid chemical fertilizers, they use compost and animal manure, which is bulkier and more expensive to ship. This also means their crop yield is usually lower. Conventional farming also uses every acre of farmland to grow crops, while organic farmers rotate their crops to keep soil healthy.

All of these production costs mean organic farming tends to be more expensive than conventional farming, and this is reflected in how much you pay at the grocery store. However, when you take into account the true “cost” of food production from conventional farming, including replacement of eroded soils, cleaning up polluted water, health care for farmers who get sick, and environmental costs of pesticide production and disposal, organic farming might actually be cheaper in the end.

Probably the most “green” way to acquire your weekly provisions is through a local farmer’s market. The food travels a shorter distance, which means less carbon emissions and food that hasn’t been shipped hundreds of miles or processed to keep it preserved during transport. The food comes from small farms where the farmers are usually conscious of their impact on the earth and care about the food they’re producing. By purchasing food from them, you also support the local food economy and know where your food is coming from. According to the Center for Urban Education about Sustainable Agriculture, food in the United States travels an average of

1,500 miles to make it to your refrigerator. Why take an apple off the truck when you’re a step away from plucking it off the tree?