Earth Ships: Intro to earth-rammed construction

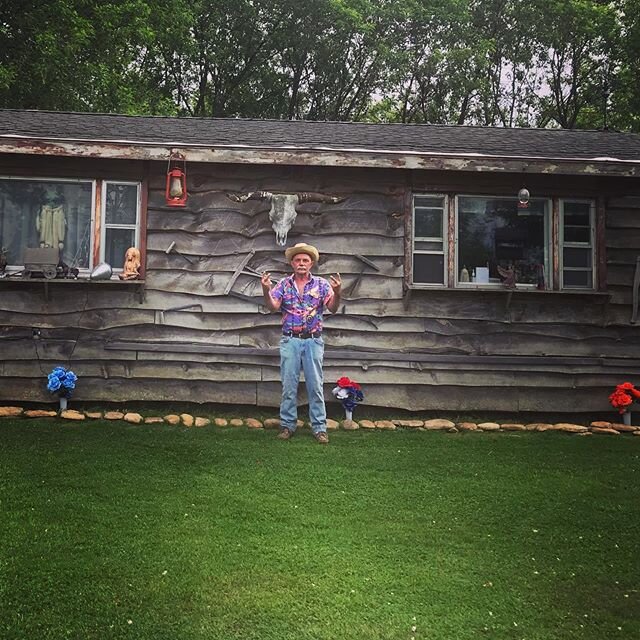

/Jackson Pittman

We've been taking on a lot of projects at Better Farm since the garden doesn't require as much maintenance. The hobbit house area is being cleared for its construction in the spring, and the mandala garden is being designed so that the base can be laid out before winter.

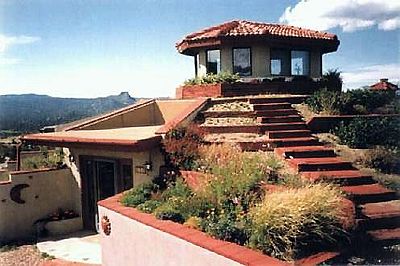

Another project we've been working on, is the creation of our Earth Ship, which is a personal favorite of mine because of the construction techniques and use of available resources. Indeed, the Earth Ship construction process may well stand as a model for the hobbit house when it comes to creating the essential earth rammed tires, a cost-effective and environmentally efficient (although labor intensive) construction material. Read on to learn more about the origins and regulations of rammed earth construction!

Origins of Earth-Rammed Construction

Believe it or not, although building things out of the earth may seem like a modern "alternative" to more traditional materials such as wood and brick, earth-rammed construction is actually a much older practice with surprising benefits. The earliest recorded city in history, Jericho, was built out of earth; and ancient Egyptian cities, Middle Eastern mosques and temples, and those in ancient China all used earth not only to build houses, but also to construct the template of the Great Wall.

Romans and Phoenicians brought the method to Europe, where it was used for a couple thousand years. In the United States, houses until 1850 were made out of earth. These were eventually replaced by wood and brick, which were mass-produced and took less time to build houses with. This continued until the Great Depression, when there was a shortage on such building materials and the idea of people creating their own houses from available resources became appealing again. However, at this time the process of building earth houses had been somewhat forgotten, so the Department of Agriculture published a manual called

Rammed Earth Walls for Buildings, and hundreds of journals and magazine articles were published regarding the topic of earth-rammed construction.

After the second world war, factories began to produce materials that were faster to construct with. Once again, earth building was forgotten until the 1970s when it was popularized among the environmentally conscious by Michael Reynolds. His technique of using tires for rammed-earth construction became increasingly practical as time went on due to their amazing benefits. The thick, dense walls of tires filled with earth are virtually soundproof, fireproof, rot resistant and impervious to termites. Aside from that, they are made to withstand temperature swings, and use 80 percent less energy.

And now, here at Better Farm, we are in the process of constructing our first earth ship! We are doing our part in fortifying the foundation for an environmentally efficient future! We described in a previous post the basic, step-by-step process of building an Earth Ship. But as we dig deeper into the procedure, we have run across a couple of road blocks.

The first was when stacking tires on top of one another, how to stop dirt from falling out the cracks where the holes in the tires don't entirely overlap. The answer to this, solved through a little research, is a common resource we utilize here at Better Farm: cardboard! Simple as that, if earth is falling out of the tires on the second row of your ship or higher, simply place cardboard along the bottom of said tire to keep the earth packable.

The second problem we came across was the most efficient way to pack the tires completely; after all if the tires aren't fully packed they don't provide the necessary insulation, and the backside of the shovel is not the most efficient or compatible packing tool for those hard to reach tire corners. The solution is once again an easy fix with a tool we use on farm anyway: the sledgehammer! It makes so much sense but it had slipped our minds when trying to figure out how to pack the tires as much as possible, but now that we know, it works like a charm.

When doing a homemade construction project like this, you really can't afford to make any mistakes, so as tedious as it can be, it's truly necessary to pack the tires as much as possible and make sure you're doing things the safe and proper way. That's why we had to remodel the bottom tire layer even though most of the tires had been already been painstakingly packed. We had overlooked the crucial ingredient of tire size. One of the most important safety regulations when building something like this is that it is architecturally sound. Now the entire bottom layer of our Earth Ship has tires 29+ inches in diameter to make sure the foundation is solid and supportive. That is necessary for an Earth Ship six layers high and although we don't plan on making ours that high its good to have stability. In addition, another thing we learned is that the tires need to stand on level soil, free of organic matter such as weeds and roots to ensure there will no rotting. More regulations from the tire building code: Tire walls over six courses high must have a ground course of tires #15 or larger exclusively. Safe and productive building to all!