|

| Better Farm's garden rows get ready for winter. We piled about 1.5 feet of hay over each row this morning. |

After reading Ruth Stout's

How to Have a Green Thumb Without an Aching Back, I was convinced of the benefits of mulch gardening; a layering method that mimics a forest floor and combines soil improvement, weed removal, and long-term mulching in one fell swoop. Also called lasagna gardening or sheet mulching, this process can turn hard-to-love soil rich and healthy by improving nutrient and water retention in the dirt, encouraging favorable soil microbial activity and worms, suppressing weed growth, and improving the well-being of plants (all while reducing maintenance!).

This is the close of our second gardening season at Better Farm, and to say it's been a crash-course in everything organic is an understatement. We've been working uphill since Day One, when we "broke ground" (and several shovels) in the clay-rich, hard earth that had only homed hay for at least half a century.

Since that time, we've experimented with several planting, growing, weeding, fertilizing, and pest-control tactics. And what began as a small

vermicompost bin in the kitchen has turned into a huge garden full of layered mulch rotting beautifully into dark, rich soil that feeds hundreds of plants every spring, summer, and fall.

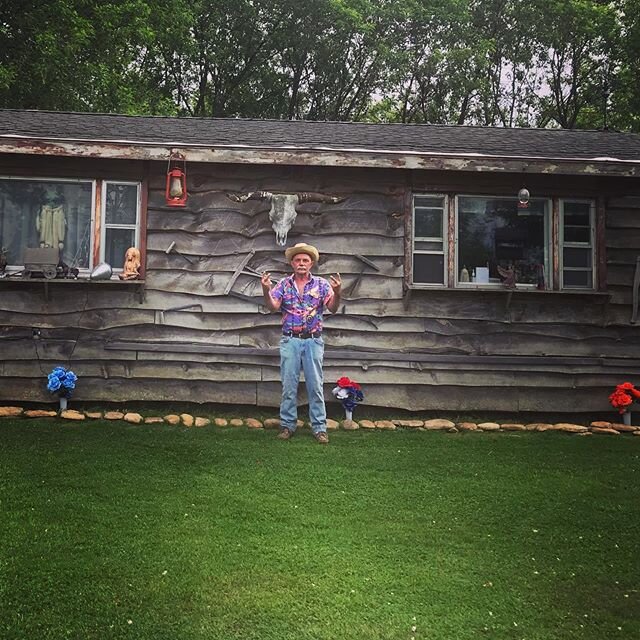

We were fortunate enough this year to be visited by Guy Hunneyman, who dropped off several bales of hay for us to use as we ready the garden for winter. Mike and I hit the garden this morning and spread the hay out into nice, thick layers.

So, how do you get to this point? First, a weed barrier like cardboard is laid down to smother weeds. The cardboard decomposes after the weeds have all died and turned into compost. On top of the cardboard you can pile dead leaves, grass clippings, compost, several-years-old composted manure, and other biodegradables such as old hay. Mulch gardening can range from just a few inches thick to 2 feet or more, depending on how bad your soil is and how much raw material you have available (it will cook down and settle quite a bit). The cyclical process goes on year-round and works so well we don't have to put a single additive or chemical into the soil.

Want to learn more? Here's a snippet from an old interview with the

Queen of Mulch herself, talking about how you too can have a green thumb without an aching back.

My no-work gardening method is simply to keep a thick mulch of any vegetable matter that rots on both my vegetable and flower garden all year round. As it decays and enriches the soil, I add more. The labor-saving part of my system is that I never plow, spade, sow a cover crop, harrow, hoe, cultivate, weed, water or spray. I use just one fertilizer (cottonseed or soybean meal), and I don't go through that tortuous business of building a compost pile.

I beg everyone to start with a mulch 8 inches deep; otherwise, weeds may come through, and it would be a pity to be discouraged at the very start. But when I am asked how many bales (or tons) of hay are necessary to cover any given area, I can't answer from my own experience, for I gardened in this way for years before I had any idea of writing about it, and therefore didn't keep track of such details.

However, I now have some information on this from Dick Clemence, my A-Number-One adviser. He says, "I should think of 25 50-pound bales as about the minimum for 50 feet by 50 feet, or about a half-ton of loose hay. That should give a fair starting cover, but an equal quantity in reserve would be desirable." That is a better answer than the one I have been giving, which is: You need at least twice as much as you would think.

What Should I Use for Mulch?

Spoiled or regular hay, straw, leaves, pine needles, sawdust, weeds, garbage — any vegetable matter that rots.

Don't Some Leaves Decay Too Slowly?

No, they just remain mulch longer, which cuts down on labor. Don't they mat down? If so, it doesn't matter because they are between the rows of growing things and not on top of them. Can one use leaves without hay? Yes, but a combination of the two is better, I think.

What is spoiled hay? It's hay that for some reason isn't good enough to feed livestock. It may have, for instance, become moldy — if it was moist when put in the haymow — but it is just as effective for mulching as good hay, and a great deal cheaper.

Shouldn't the hay be chopped?

Well, I don't have mine chopped and I don't have a terrible time — and I'm 76 and no stronger than the average person.

Can you use grass clippings?

Yes, but unless you have a huge lawn or neighbors who will collect them for you, they don't go very far.

How Do You Sow Seeds into the Mulch?

You plant exactly as you always have, in the Earth. You pull back the mulch and put the seeds in the ground and cover them just as you would if you had never heard of mulching.

How Do You Sow Seeds into the Mulch?

You plant exactly as you always have, in the Earth. You pull back the mulch and put the seeds in the ground and cover them just as you would if you had never heard of mulching.

How Often Do You Put on Mulch?

Whenever you see a spot that needs it. If weeds begin to peep through anywhere, just toss an armful of hay on them. What time of year do you start to mulch? The answer is now, whatever the date may be, or at least begin to gather your material. At the very least give the matter constructive thought at one; make plans. If you are intending to use leaves, you will unfortunately have to wait until they fall, but you can be prepared to make use of them the moment they drop. Should you spread manure and plow it under before you mulch? Yes, if your soil isn't very rich; otherwise, mulch alone will answer the purpose.

How Far Apart Are the Rows?

Exactly the same distance as if you weren't mulching — that is, when you begin to use my method. However, after you have mulched for a few years, your soil will become so rich from rotting vegetable matter that you can plant much more closely than one dares to in the old-fashioned way of gardening.

How Long Does the Mulch Last?

That depends on the kind you use. Try always to have some in reserve, so that it can replenished as needed.

Now for the Million Dollar Question: Where Do You Get Mulch?

That's difficult to answer but I can say this: If enough people in any community demand it, I believe that someone will be eager to supply it. At least that's what happened within a distance of 100 miles or so of us in Connecticut, and within a year after my book came out, anyone in that radius could get all the spoiled hay they wanted at 65 cents a bale.

If you belong to a garden club, why can't you all get together and create a demand for spoiled hay? If you don't belong to a group, you probably at least know quite a few people who garden and who would be pleased to join the project.

Use all the leaves you can find. Clip your cornstalks into footlength pieces and use them. Utilize your garbage, tops of perennials, any and all vegetable matter that rots. In many localities, the utility companies grind up the branches they cut off when they clear the wires; and often they are glad to dump them near your garden, with no charge. But hurry up before they find out that there is a big demand for them and they decide to make a fast buck. These wood chips make a splendid mulch; I suggest you just ignore anyone who tells you they are too acidic.

Recently, a man reproached me for making spoiled hay so popular that he can no longer get it for nothing. The important fact, however, is that it has become available and is relatively cheap. The other day a neighbor said to me, "Doesn't it make you feel good to see the piles of hay in so many yards when you drive around?" It does make me feel fine.

Now and then I am asked (usually by an irritated expert) why I think I invented mulching. Well, naturally, I don't think so; God invented it simply by deciding to have the leaves fall off the trees once a year. I don't even think that I'm the first, or only person, who thought up my particular variety of year-round mulching, but apparently I'm the first to make a big noise about it — writing, talking, demonstrating.

And since in the process of spreading this great news, I have run across many thousands who never heard of the method, and a few hundred who think it is insane and can't possibly work, and only two people who had already tried it, is it surprising that I have carelessly fallen into the bad habit of sounding as though I thought I originated it?

But why should we care who invented it? Dick Clemence works hard trying to get people to call it the "Stout System," which is good because it should have some sort of a short name for people to use when they refer to it, instead of having to tell the whole story each time. I suppose it does more or less give me a feeling of importance when I come across an article mentioning the Stout System, yet I am cheated out of the full value of that sensation because I've never been able really to identify the whole thing with that little girl who was certainly going to be great and famous some day. What a disgusted look she would have given anyone who would have offered her the title of Renowned Mulcher!

And it borders on the unenthralling to have the conversation at social gatherings turn to slugs and cabbageworms the minute I show up. And if some professor of psychology, giving an association-of-ideas test to a bunch of gardeners, should say "moldy hay" or "garbage," I'm afraid that some of them would come out with "Ruth Stout." Would anyone like that?

If you want to learn more about the Stout System, you can locate copies of Ruth Stout's books through a used bookseller. You also can order the VHS or DVD video Ruth Stout's Garden

from Gardenworks.