Mulch Much? The Benefits of Gardening with Mulch

/Written by Karen Lynn

So Why Mulch?

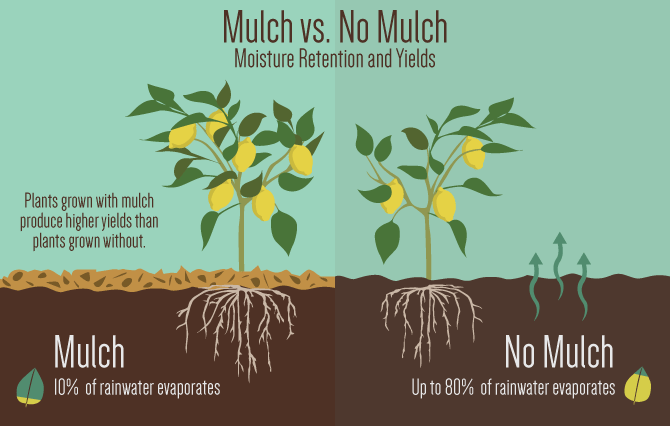

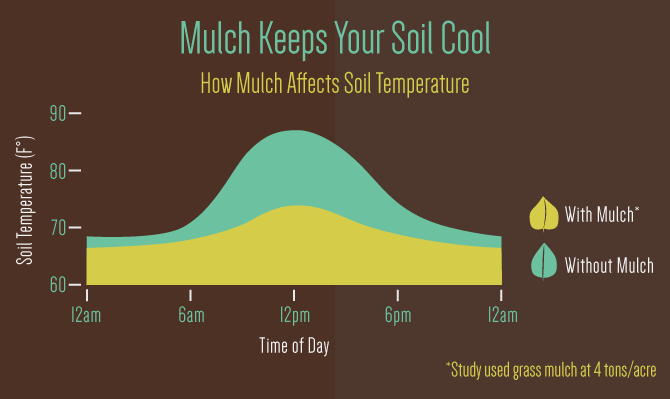

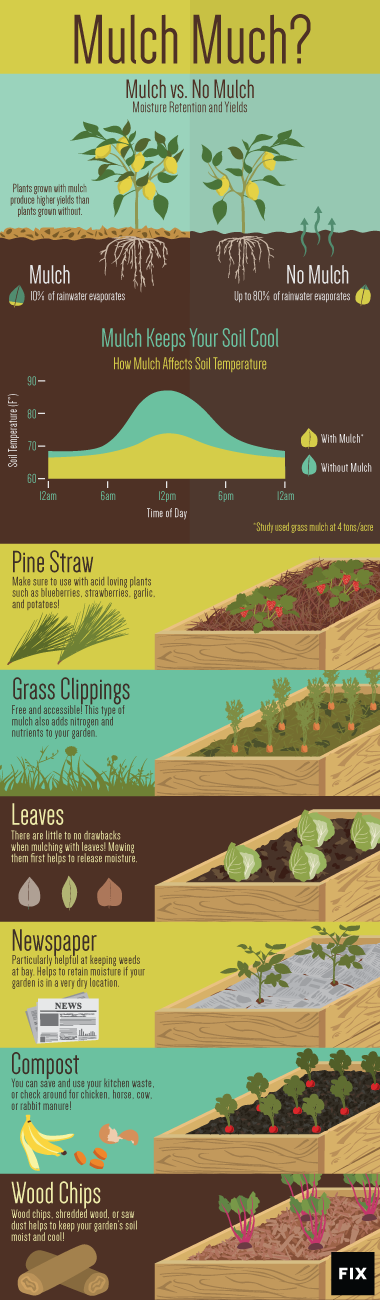

The most basic benefit of mulch is moisture retention. Yields are directly affected by the amount of water in the soil. And, in dryer climates where rainfall is scarce, gardeners will want their soil to retain as much water as possible. Simply by covering the top of the soil in a thin layer of organic material, you will drastically reduce the level of moisture evaporated from the soil. The graphic below shows just how dramatically mulching can reduce evaporation. Mulching can retain up to 80% of added moisture in your soil. When you keep the top of the soil protected from direct heat, it will lose less water, and thus be a better environment for your plants. Great mulch also has the ability to breathe, and not become a place where mold issues arise, which would be unhealthy for plant life.Compost is technically not mulch, but rather a soil amendment, an additive used to increase soil nutrition. Compost can also be used as a top dressing. It is a very significant component of a great garden, so it is good to keep it in mind as part of your gardening efforts.

Different Types of Mulches

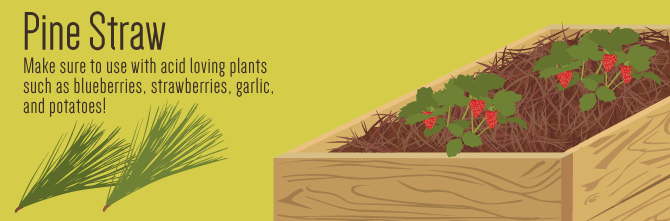

There are many different types of mulch, and some of these cost little to nothing. Some common mulches are pine straw, grass clippings, leaves, newspapers, and wood chips.Pine straw makes for fabulous mulch, but you have to make sure you place pine straw near acid-loving plants. In some parts of the country pine straw is an abundant free resource, and is very convenient to collect. Many acid-loving fruits and vegetables benefit from pine straw mulch, including blueberries, strawberries, garlic, tomatoes, and potatoes. A drawback to pine straw mulch is that it can be messy, the color fades very quickly, and it’s very flammable.

Grass clippings also make fabulous mulch; the best part being that they are free and accessible. Furthermore, you are re-distributing garden and lawn matter to other areas of your garden, which carries the added benefit of providing a place to dispose of that matter. The grass clippings will add nitrogen and much needed nutrients for beneficial microbes that inhabit the soil, which your plants will love.

A word of caution about removing grass clippings from the side of the road: you must be sure that the grass is not chemically laden with fertilizers and pesticides. The only other issue that could crop up is that if the clippings come from a weedy area you may be transferring weeds or undesirable plants unknowingly.

Leaves are a favorite mulch of many gardeners. There are few to no drawbacks when mulching with leaves, and they can be spread to protect your soil during winter months. Oak and maple leaves in particular are popular mulch material because they are plentiful. Mowing over the leaves turns them into shredded mulch, which helps release some moisture, and also makes them easier to spread. Many times, leaves are free for the taking since most folks won’t mind you raking their lawns for them, and that will happily load you up with your fill of mulch!

Next up is newspaper. Your first thought might be “ugh!” but there is a place in the garden for non-colored and non-magazine-type newsprint. It’s inexpensive, available, and can often be found at your local recycling bin. Newspaper is a very easy and efficient way to keep weeds at bay as well as assisting to keep the soil moist. It is particularly helpful when you have not been able to amend your soil as well as you would like too, or if your garden plot is in an extremely dry location with lots of drainage. You will want to wet your newspaper down when you use it and you will need to place another type of mulch on top, possibly mixed with some amended soil and compost, to help hold the newspaper down.

Composting is basically decomposing your kitchen trash from fresh foods such as vegetable scraps, egg shells, whole grains, any green growing material, chicken, horse, cow, or rabbit manure (but not household pet waste), and any dried matter in the garden. Often, local horse farms will gladly let you come collect their manure right out of the barns or pastures and in many cases you can barter with friends, neighbors, or your local farmer for chicken or rabbit manure. Rabbit manure can be put straight into the garden and is often referred to as “Gardeners Gold.”

Another mulch option is wood chips, shredded wood, or saw dust; however it is important to note that you should not use treated wood as it is loaded with chemicals and not good for you or your garden. There is debate over whether you should place fresh wood chips in your garden, and popular opinion is on both sides of the fence. Some folks say the fresh wood chips rob the soil of much-needed nitrogen and other folks argue that the fresh wood chips may decrease nitrogen initially but then it cycles back to the soil by naturally breaking down and amending the soil. Whatever you decide in the end, wood is nice and heavy and it will keep the soil moist and cool along with keeping weeds away from your beautiful plants.

Reducing the Cost

You may find mulching to be expensive, and it could be, if your garden is large and you don’t have any of the six mulches above at your disposal. But many communities have options for free mulch: some communities have yard debris recycling programs that turn debris into mulch, allowing citizens to gather it for free or a very small cost. Sometimes tree companies give away shredded branches as mulch. Landfills may have some free mulch options as well. Check online forums and hardware store bulletin boards for options in your local area. Mulching is probably not out of your reach.Storing Mulch

When gathering mulch in the fall or winter when it is more readily available, you need to address storing the mulch for spring and summer use. The most important issue when storing mulch is to keep it dry. If the mulch is completely dry then you could store it in plastic bins, trash bags, or trash cans. If the mulch is not dry then your next best option would be to pile it up in the yard in an out-of-the-way location and turn it frequently until it dries out, then store in bins or bags.Placing Mulch in the Garden

Placing mulch in the garden should be done very strategically. For example, wait until most of your seedlings sprout through the top soil: this allows time for any volunteers to poke through the ground, for transplanting elsewhere in the garden. It is also a good idea to add more mulch halfway through the gardening season and to spot-check your gardening areas from time to time so you can ensure the soil for your plants is staying moist.Mulch is an often-free, valuable resource for the success of a garden. It keeps your roots moist, adds beneficial nutrients to the soil, and can really make the difference to an abundant garden. Take the time to experiment with different mulches, keeping note of which mulches work best with your plants. Also, to have your garden soil tested, contact your local agricultural extension office or check out our soil testing article, to make sure you are using the ideal mulch for your garden.

To sum up, it pays to consider the best mulch option for your garden situation and conditions. Consider your soil requirements, your space requirements and your wallet. Your payoff is in abundant plant production. I wish you much success as you add beneficial nutrients and just the right amount of ongoing moisture by using mulch.

Have you mulched much lately?