From the Redwoods to Redwood

/ |

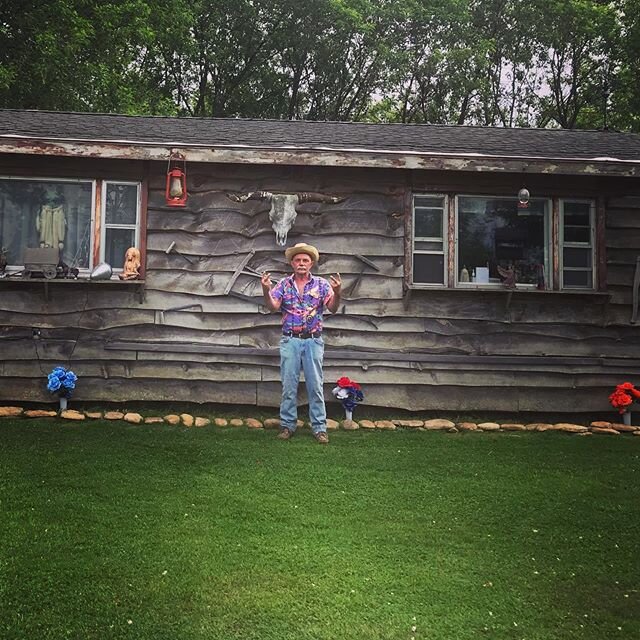

| Arnie Nova, a technician for the Yurok Fisheries Department in Klamath, Calif., visits Better Farm this week. |

Klamath is a rural town situated on US Route 101 in Del Norte County, about 300 miles north of San Francisco. In addition to being the home base for many Yurok tribal offices, Klamath is nestled amidst the Redwood Forest—and is home to this iconic roadside attraction any of you who have road-tripped up the California coast have seen:

|

| Paul Bunyan and his legendary sidekick Babe, a 35-foot blue ox. The statues stand side by side at the entrance to Redwood Forest tourist attraction Trees of Mystery. |

Since meeting Arnie in 2001, I've had the pleasure of visiting him more than a half-dozen times in and around Klamath. I've protested with the Yuroks in Portland in an effort to shut down dams; accompanied the tribe on sturgeon-tracking ventures, attended tribal ceremonies, and smoked salmon on the beach where the Klamath River meets the Pacific Ocean.

|

| Arnie and me. |

Warmest welcomes to my dear old friend! Here's some more background on the Yuroks. For further reading and to learn how you can help support Arnies mission out west, visit www.yuroktribe.org.

The Yurok Tribe

At one time, the Yuroks

lived in more than 50 villages throughout our ancestral territory. The

laws, health and spirituality of our people were untouched by

non-Indians. Culturally, Yuroksare known as great fishermen, eelers, basket weavers, canoe-makers, storytellers, singers, dancers, healers and strong medicine

people.

The Klamath-Trinity River is the lifeline of the Yuroks people because the majority of the food supply, like ney-puy (salmon), Kaa-ka (sturgeon) and kwor-ror (candlefish) are offered from these rivers. Also important to Yuroks are the foods which are offered from the ocean and inland areas such as pee-ee (mussels), chey-gel’ (seaweed), woo-mehl (acorns), puuek (deer), mey-weehl (elk), ley-chehl (berries), and wey-yok-seep (teas). These foods are essential to the Yuroks' health, wellness, and religious ceremonies. The Yurok way was never to over harvest and to always ensure sustainability of the food supply for future generations.

Traditional family homes and sweathouses are made from fallen keehl

(redwood trees) which are then cut into redwood boards. Before contact,

it was common for every village to have several family homes and

sweathouses. Today, only a small number of villages with traditional

family homes and sweathouses remain intact. Yurok traditional stories

teach that the redwood trees are sacred living beings. Although Yuroks

use these trees in their homes and canoes, they also respect redwood trees because

they stand as guardians over sacred places.

The traditional money used by Yurok people is terk-term (dentalia shell), which is a shell harvested from the ocean. The dentalia used on necklaces are most often used in traditional ceremonies, such as the u pyue-wes (White Deerskin Dance), woo-neek-we-ley-goo (Jump Dance) and mey-lee (Brush Dance). It was standard years ago, to use dentalia to settle debts, pay dowry, and purchase large or small items needed by individuals or families. Tattoos on men’s arms measured the length of the dentalia.

The traditional money used by Yurok people is terk-term (dentalia shell), which is a shell harvested from the ocean. The dentalia used on necklaces are most often used in traditional ceremonies, such as the u pyue-wes (White Deerskin Dance), woo-neek-we-ley-goo (Jump Dance) and mey-lee (Brush Dance). It was standard years ago, to use dentalia to settle debts, pay dowry, and purchase large or small items needed by individuals or families. Tattoos on men’s arms measured the length of the dentalia.

EXPLORATION AND SETTLEMENT

Yurok did not

experience non-Indian exploration until much later than other tribal

groups in California and the United States. One of the first documented

visits in the local area was by the Spanish in the 1500s. When Spanish

explorers Don Bruno de Heceta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Cuadra

arrived in the early 1700s, they intruded upon the people of Chue-rey

village. This visit resulted in Bodega laying claim by mounting a cross

at Trinidad Head.

In the early 1800s, the first American ship visited the area of Trinidad and Big Lagoon. Initially, the Americans traded furs with the coastal people. However, for unknown reasons tensions grew and the American expedition was cut short. The expeditions increased over the next few years and resulted in a dramatic decrease of furs in the area.

By 1828, the area was gaining attention because of the reports back from the American expeditions, despite the news that the local terrain was rough. The most well-known trapping expedition of this era was led by Jedediah Smith. Smith guided a team of trappers through the local area, coming down through the Yurok village of Kep’-el, crossing over Bald Hills and eventually making their way to the villages of O men and O men hee-puer on the coast.

Smith’s expedition, though

brief, was influential to all other trappers and explorers. The reports

from Smith’s expedition resulted in more trappers exploring the area and

eventually leading to an increase in non-Indian settlement.

GOLD RUSH IN YUROK COUNTRY

By 1849 settlers were

quickly moving into Northern California because of the discovery of gold

at Gold Bluffs and Orleans. Yurok and settlers traded goods and Yurok

assisted with transporting items via dugout canoe. However, this

relationship quickly changed as more settlers moved into the area and

demonstrated hostility toward Indian people. With the surge of settlers

moving in the government was pressured to change laws to better protect

the Yurok from loss of land and assault.

The rough terrain of the local area did not deter settlers in their pursuit of gold. They moved through the area and encountered camps of Indian people. Hostility from both sides caused much bloodshed and loss of life.

The gold mining expeditions resulted in the destruction of villages, loss of life and a culture severely fragmented. By the end of the gold rush era at least 75% of the Yurok people died due to massacres and disease, while other tribes in California saw a 95% loss of life.

TREATY NEGOTIATIONS

While miners established

camps along the Klamath and Trinity Rivers, the federal government

worked toward finding a solution to the conflicts, which dramatically

increased as each new settlement was established.

The government sent Indian agent Redick McKee to initiate treaty negotiations. Initially, local tribes were resistant to come together, some outright opposed meeting with the agent. The treaties negotiated by McKee were sent to Congress, which was inundated with complaints from settlers claiming the Indians were receiving an excess of valuable land and resources.

The Congress rejected the treaties and failed to notify the tribes of this decision.

REVOLTS AGAINST SETTLERS

In 1855, a group of “vigilante” Indians (who were known as Red Cap Indians) initiated a revolt against settlers.

In 1855, a group of “vigilante” Indians (who were known as Red Cap Indians) initiated a revolt against settlers.

The Red Cap Indians were believed to be a mix of tribal groups who were fighting settlers.

The Red Cap War nearly brought a halt to the non-Indians settlement effort.

The government was able to suppress the Red Cap Indians and regained control over the upper Yurok Reservation.

FORMATION OF RESERVATIONS

The Federal Government

established the Yurok Reservation in 1855 and immediately Yurok people

were confined to the area. The Reservation was considerably smaller than

the Yurok original ancestral territory. This presented a hardship for

Yurok families who traditionally lived in villages along the Klamath

River and northern Pacific coastline.

When Fort Terwer was established many Yurok families were relocated and forced to learn farming and the English language. In January 1862, the Fort was washed away by flood waters, along with the Indian agency at Wau-kell flat. Several Yurok people were relocated to the newly established Reservation in Smith River that same year.

However, the Smith River Reservation was closed in July 1867. Once the Hoopa Valley Reservation was established many Yurok people were sent to live there, as were the Mad River, Eel River and Tolowa Indians.

In the years following the opening of the Hoopa Valley Reservation, several squatters on the Yurok Reservation continued to farm and fish in the Klamath River. The government’s response was to evict squatters and use military force. Many squatters did not vacate and waited for military intervention, which was slow to come. In the interim, the squatters pursued other avenues to acquire land.

COMMERCIAL LOGGING

The Fort and Agency were built from redwood, which was an abundant resource and culturally significant to Yurok. Non-Indians pursued the timber industry and hired local Indian men to work in the up and coming mills on the Reservation. This industry went through cycles of success, and was largely dependent on the needs of the nation. At the time, logging practices were unregulated

and resulted in the contamination of the Klamath River, depletion of

the salmon population and destruction of Yurok village sites and sacred

areas.

COMMERCIAL CANNERIES

The Yurok canneries were established near the mouth of the Klamath River beginning in 1876.

The Yurok people opposed non-Indians taking of

the salmon and asserted that they did not have the right to take fish

from the river because it is an inherent right of the Yurok people.

WESTERN EDUCATION

Western education was

imposed on Yurok children beginning in the late 1850s at Fort Terwer and

at the Agency Office at Wauk-ell. This form of education continued

until the 1860s when the Fort and Agency were washed away.

Yurok children, sent to live at the Hoopa Valley Reservation, continued to be taught by missionaries. The goal of the missionary style of teaching was to eliminate the continued use of cultural and religious teachings that Indian children’s families taught. Children were abused by missionaries for using the Yurok language and observing cultural and ceremonial traditions.

In the late 1800s children were removed from the Reservation to Chemawa in Oregon and Sherman Institute in Riverside, California. Today, many elders look back on this period in time as a horrifying experience because they lost their connection to their families, and their culture. Many were not able to learn the Yurok language and did not participate in ceremonies for fear of violence being brought against them by non-Indians. Some elders went to great lengths to escape from the schools, traveling hundreds of miles to return home to their families. They lived with the constant fear of being caught and returned to the school. Families often hid their children when they saw government officials.

Over time the use of boarding schools declined and day schools were established on the Yurok Reservation. Elders recall getting up early in the morning, traveling by canoe to the nearest day school and returning home late at night. The fact that they were at day schools did not eliminate the constant pressure to forget their language and culture.

Families disguised the practice of teaching traditional ways, while others succumbed to the western philosophy of education and left their traditional ways behind. Eventually, Indian children were granted permission to enroll in public schools. Although they were granted access, many faced harsh prejudice and stereotypes. These hardships plagued Indian students for generations, and are major factors in the decline of the Yurok language and traditional ways. The younger generations of Yurok who survived these eras became strong advocates (as elders) for cultural revitalization.

LANGUAGE REVITALIZATION

The use of

the Yurok language dramatically decreased when non-Indians settled in

the Yurok territory. By the early 1900s the Yurok language was near

extinction. It took less than 40 years for the language to reach that

level. It took another 70 years for the Yurok language to recover. When

the language revitalization effort began the use of old records helped

new language learners. However, it was through hearing fluent speakers

that many young learners fluency level increased.

When the Yurok Tribe began to operate as a formal tribal government a language program was created. In 1996 the Yurok Tribe received assistance from the Administration for Native Americans (ANA). With the development of a Long Range Restoration Plan a survey was completed and the results showed that there were only 20 fluent speakers and 12 semi-fluent speakers of the Yurok language. After a decade of language restoration activities, the Tribe most recently documented that there are now only 11 fluent Yurok speakers, but now have 37 advanced speakers, 60 intermediate speakers and approximately 311 basic speakers. The Yurok Tribe continues to look to new approaches like the use of digital technology, internet sites, short stories, and supplemental curriculum. The Tribe continues to increase the number of language classes taught on and off the Reservation, at local schools for young learners and at community classes.

TODAY

The Yurok

Tribe is currently the largest Tribe in California, with more than 5,000

enrolled members. The Tribe provides numerous services to the local

community and membership with its more than 200 employees. The Tribe’s

major initiatives include: the Hoopa-Yurok Settlement Act, dam removal,

natural resources protection, sustainable economic development

enterprises and land acquisition.