Bank the Farm: Let it Snow!

/ Northern

New York has finally been enjoying a “real winter” of snowfalls up to

three feet at a clip. It's made for great shoveling adventures:

driveways, decks, igloo and snowman construction. But actually packing

that snow against your house (called “banking”) can help to insulate it

all winter long (or, at least until it thaws!).

Northern

New York has finally been enjoying a “real winter” of snowfalls up to

three feet at a clip. It's made for great shoveling adventures:

driveways, decks, igloo and snowman construction. But actually packing

that snow against your house (called “banking”) can help to insulate it

all winter long (or, at least until it thaws!).Unless you live in a real wintry tundra where there's no thaw until March, banking your home will probably have to be done after every heavy snowfall. But even if you pick just one wall of your house, the benefits are great — especially if your home is prone to winter drafts. Before home insulation was a widespread practice, many farmers lined their foundations with hay or straw bales to accomplished the same thing as snow-banking.

Understanding the key principles of home insulation is a must for anyone trying to do a better job of keeping the heat inside. Insulation works by slowing down heat movement through building materials. Heat will always move to a colder source. In the winter, insulation keeps heat in. In summer, insulation keeps heat out. The result in both climates is energy saved by keeping the air conditioner or heat source from operating as often.

Insulation is measured by its R-value, which allows you to calculate how much heat will move through a certain wall area depending on the temperature difference between the indoor and the outdoor air. The R-value of insulation is a measure of thermal resistance, expressed as the thickness of the material divided by the thermal conductivity. The higher the number, the better the insulation's effectiveness.

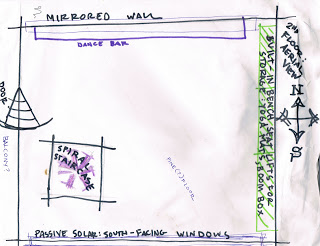

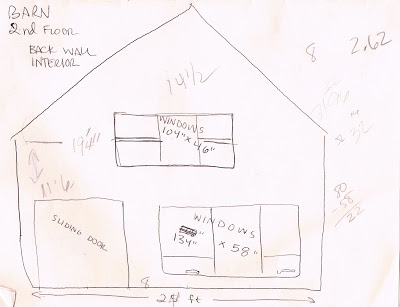

To bank your house, you'll want to have enough snow to make at least two-foot mounds along the outside walls. For every inch of snow, you gain an R-value of 1 or more. Most older homes are still outfitted with R-11 insulation on their walls; newer homes often have wall insulation with R-13 or higher. Banking your house will provide you with several additional R-value degrees on the walls — saving you significant dollars on energy costs or insulation-replacement costs).

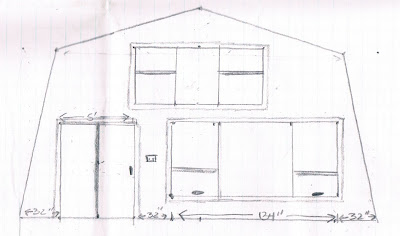

Grab a snow shovel (or several—many hands make light work), and mound up snow two feet or higher along the sides of the building. Some people find it's easier to pack snow against their house by using a sheet of plywood (4x6 or 4x8) held vertically two feet away from the outside wall of the house and a pole that is strong enough to support the wooden sheet. Start at the corner of the house and pack snow between the plywood and house, moving the plywood and pole along as you fill in the gap.

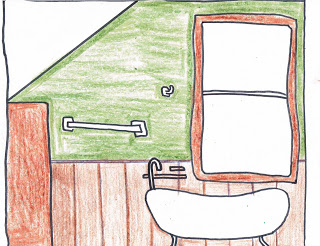

This is especially effective when you can bury the foundation—stone being a conductor of heat—in snow. It also seals whatever tiny cracks allow cold to enter.

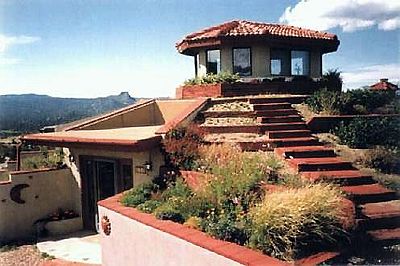

Decking or stairs may prevent banking at certain locations of your house; but wherever you can, bank. You are guaranteed to feel the difference.